Tehran-IRAF- the 72‑minute documentary recounts the life of Mohsen Mirza’ei, an Afghan fighter of the Sacred Defense—one who was wounded during Operation Karbala‑4 and later captured by Ba’athist forces.

Mohsen (Mirzaei) “the Japanese” is one of thousands of Afghan fighters who were present during the Iran‑Iraq War and made sacrifices in defense of the land of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

The story of Mohsen Mirzaei is, in truth, the story of thousands of Afghan fighters of the Sacred Defense—fighters who, from Dasht‑e‑Leili to Majnoon Island, fought without expectation of reward and stood firmly by the lofty ideals of the Islamic Revolution.

A Fighter from Japan or Afghanistan?

Mohsen “the Japanese” says he was born in (1969) in Kabul, but his parents migrated to Iran around the time of the Islamic Revolution (1979). He recalls:

“Around the shrine and Shohada Square, I had a small toy shop and worked to help support my family.”

He continues: “Whenever news spread in Mashhad that forces were being deployed, I would pack up my shop, throw it over my shoulder, and run toward the railway station just to watch the convoys of fighters. Seeing the passion and excitement in their eyes swept me away. I always dreamed of being one of them and going to the front.”

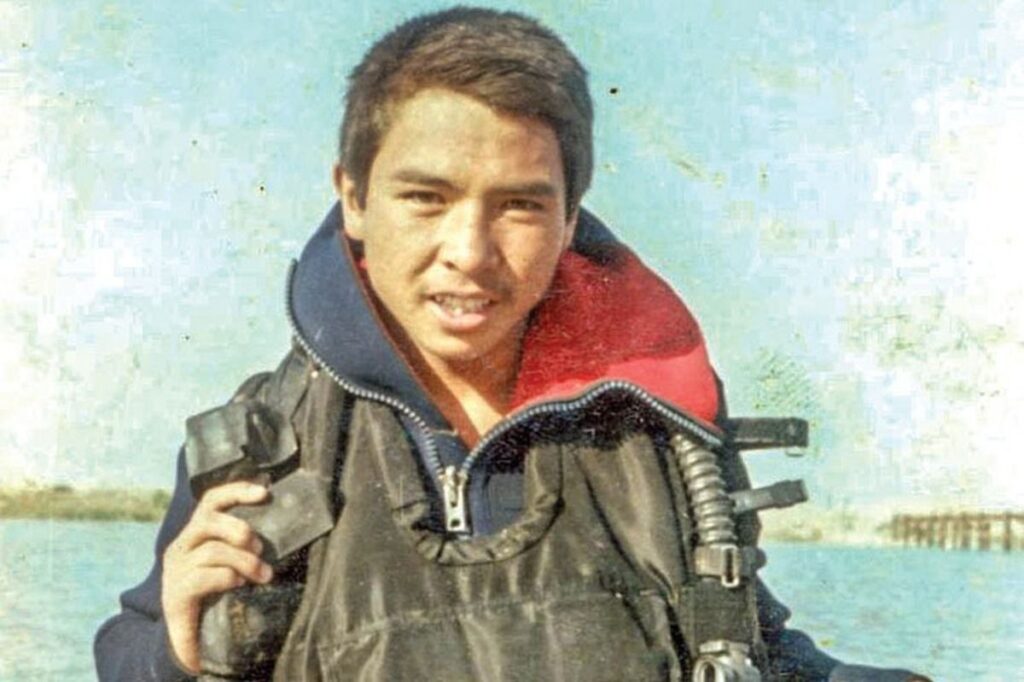

Two serious obstacles stood in Mohsen Mirzaei’s way: his short height and his Afghan nationality. But going to the front requires heart—and when there is will, a way is found. He altered his identification card and added a few years to his age. Although teenagers were usually turned back before deployment, Mohsen succeeded in fulfilling his dream and made his way to the front lines.

From the Front Lines to Karbala‑4

Before Operation Kheibar in 1983, Mohsen arrived at Zafar Camp in Ilam and initially went to the front as an assistant RPG gunner. Just days later, he was a fourteen‑year‑old boy holding an RPG, standing near Hoor al‑Azim.

From there, he participated in multiple operations: Meymak, Badr, Valfajr‑8, and Karbala‑1. In the final three operations, he served as a diver, and in Operation Karbala‑4, he advanced as the deputy leader of the penetration unit.

Karbala‑4; Shalamcheh

During Operation Karbala‑4, Mohsen Mirzaei was assigned a heavy responsibility within the penetration unit—an assignment simple in description yet deadly in reality: breaking the enemy line and opening the way for the forces behind them. He says:

“There was no other way; we had to enter the water and open the path.”

Less than an hour passed before the Arvand River filled with lifeless bodies. The only way to survive was to cross a minefield—someone had to clear the path.

Mohsen emerged from the water. He knew that crawling would make him an easy target, so he ran. He crossed the minefield, but the flesh of his thigh caught on barbed wire. Wounded and bleeding, he sat among the reeds. Ahead of him lay the enemy’s supply road and machine guns mowing down the fighters in the water.

Five divers reached him, reviving hope—until a bullet tore through his face and another burned into his shoulder. Mohsen collapsed and lost consciousness. When he opened his eyes the next morning, he was still alive.

“Yabani! Yabani!”

The Iraqis arrived over him. One of them removed his diving hood, stared for a few seconds, then suddenly shouted: “Yabani!”—Japanese.

That single word changed Mohsen’s fate. Just as they were about to finish him off, an order came to keep him alive. The Iraqis believed they had captured a foreign soldier.

Mohsen was not afraid of death. Under his diving suit, he had hidden two pieces of paper—one containing his real identity and the other holding coded identification information. If these were discovered, torture without end awaited him.

In the restroom of an abandoned school, with a bullet‑wounded hand, he shredded the papers and threw them into a pit. Parched and barely alive, he drank contaminated water from a pitcher and returned. Now he was just a prisoner—no longer someone carrying classified information.

From that day on, his name became “Mohsen the Japanese.” Wherever he was transferred, cameras awaited him. The Baathists wanted a confession—that Iran was using foreign forces. For four years, he sat in front of cameras—under torture, cables, and humiliation—repeating only one sentence:

“I am not Japanese.”

The Tunnel of Death; The Fate of the Missing

Mohsen’s captivity lasted until 1990. His worst days were spent in Takrit Camp 11, the prison of the missing. The Tunnel of Death—where prisoners were forced to pass between rows of Baathists, beaten with cables and clubs.

Everyone was beaten—but he was beaten more, because he was “Japanese,” “Korean,” “Filipino”—anything but Iranian.

His friends wasted away before his eyes. Wounds became infested, thirst brought tears, and names like Mohammad Reza Shafiei became immortal in those cells.

In the fourth year, the tide turned. After the ceasefire resolution and the passing of Imam Khomeini (ra), news of freedom arrived. The Red Cross entered the camp. The cables fell to the ground. Paper and pens were distributed, and they were told:

“You may go wherever you want—America, Europe, anywhere.”

Among two thousand prisoners, all but a few gave the same answer:

“Iran.”

Mohsen the Japanese—an Afghan fighter—returned as a freed prisoner of war, with 50 percent disability, to the country for which he had fought.

Iran and Afghanistan; One Nation in Two Countries

The story of Mohsen the Japanese is the story of people who stood firm in defense of Islam and the Revolution to the very end. Mohsen Mirzaei is only one of thousands of Afghan fighters who played a prominent role in the Sacred Defense and who, alongside Iranian fighters, were martyred, wounded, or taken captive.

The blessed days of Daheye Fajr ( Ten Days of Dawn)are an opportunity to remember the lofty ideals of the Islamic Revolution—ideals that remind us that Islam recognizes no borders.

The presence of thousands of Afghan fighters in the imposed war was not merely a military cooperation between two countries. To reduce it to that would be an injustice to the martyrs.

Mohsen Mirzaei, Martyr Nasim Afghani, and more than three thousand Afghan martyrs are symbols of solidarity, empathy, and companionship between two nations—two nations that throughout history have stood shoulder to shoulder at critical and decisive moments.

Iran and Afghanistan are two nations that, were it not for political borders, would share the greatest similarities in history, culture, religion, and language.

Daheye Fajr (Ten Days of Dawn) is an opportunity to remember this truth:

the peoples of Iran and Afghanistan have always been one another’s refuge and support.